Priorat …Olé, Olé, Olé !

Voluptuous flamenco dancers in vibrantly colored costumes, complete with their rhythm setting castanets; fiercely handsome matadors; savory tapas; exotic architecture, heavily influenced by seven hundred years of Moorish presence in Andalusia, are the images we typically associate with Spain. As for Spanish wine, the name that readily pops to mind is Tempranillo – a deeply colored, fruit forward wine with hints of citrus and spices. Tempranillo, derived from the word temprano, which means early in Spanish, referring to its early ripening characteristic, is the most famous native Spanish red grape. Although Tempranillo finds its best expression, especially young, unoaked styles, in Rioja in the north (so much so that Rioja and Tempranillo are sometimes used interchangeably), it is grown throughout the Iberian Peninsula. Tempranillo, which has a long history dating back to the Phoenician settlements in and around Cadiz – the trading hub for the Phoenician merchants – is the most widely planted red variety of the country.

Notwithstanding the popularity of Rioja and Tempranillo, Spain is an impressive treasure trove of many other wine regions that offer a lot more than just Tempranillo. Endowed with nearly three million acres of vineyard land, Spain is the most widely planted country worldwide, and holds the second place in wine production after Italy. Granted, almost half of the country’s wine is produced in the central plateau that lies to the south of Madrid and consists of inexpensive reds and whites destined for international markets. However, there are several other wine regions throughout the country, encompassing different climactic zones, with well over four thousand wineries, four hundred native grapes and over one hundred and fifty appellations that produce a wide range of wines– still reds from fruity, early drinking to oak aged more complex styles, presenting a rich cross section between the old and the new world styles; refreshing still whites; world renown sherry in the south where Palomino and Pedro Ximenez are the leading varieties, as well as sparkling wine, Cava, made in the traditional style from local white grapes Parellada, Macabeo and Xarel-lo. Despite the availability of a much larger native grape pool, only a handful of white grapes are used in still white wine and Cava production. Albarino, tantalizingly fragrant with citrus and stone fruit aromas, and refreshingly high natural acidity, thrives in the cooler and damp climate of Rias Baixas in the northwest to complement the delectable seafood heavy cuisine of the area. Verdejo, Rueda’s traditional grape, also with naturally high acidity and melon and peach aromas, is produced on its own or blended with Sauvignon Blanc. Airen, the most widely planted white variety, is the only white grape that can stoically withstand the cruelly hot and dry summers of the central plateau and is mainly used in the production of inexpensive bulk wines.

While Tempranillo’s supremacy in Rioja, Ribera del Duero, and Navarra is uncontested, where diurnal temperature range helps this early ripening grape retain its acidity through the hot summer months, Garnacha, Monastrell, and Mazuelo (aka Grenache, Mourvèdre, and Carignan, respectively) are the reigning indigenous champions along the Mediterranean coast. Wine regions extending from the French border in the north to Valencia in the south, is almost a natural continuation of the southern French wine regions, where the same varietals are used often in blends with Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, or Tempranillo, for the right balance of tannins, acidity and color. In central Spain on the other hand, Bobol is the leading red which is mainly used in the production of inexpensive large volume wines, while the mountainous Bierzo region in the northwest features the lighter, delicately spicy red Mencia which is being experimented in different styles and been gaining in popularity lately.

As in Bierzo, where a new generation of winemakers are working with much lower yields to produce more complex and concentrated styles of Mencia, a nationwide effort to improve viticultural and winemaking practices has been underway in the last several decades – as is evidenced in the updating of the original Spanish wine laws of 1932, in 1970, and again as recently as in 2016.This upsurge is especially notable in Priorat. Located to the east of Barcelona in Catalunya region, Priorat is most certainly not a new kid on the block, with a long viticultural history. Catalunya’s coastal city of Tarragona was a cradle to Phoenician and Roman winemakers who have long sawn the seeds of wine culture in the area. Monks of the Carthusian Order, who established the Priorato dei Scala Dei monastery planted vineyards in Tarragona, and enjoyed the local grape juice just as much. Priorat, having gone through the destruction of phylloxera in the late nineteenth century and a period of poor winemaking practices, was put back on the map by a handful of avant-garde winemakers in the mid-1980s. As the story is affectionately told by the locals, a couple of hippies, René Barbier and Álvaro Palacios, who later joined ranks with a few other likeminded friends, are the true heroes of Priorat’s recent revival.

On a recent trip to Barcelona, I visited a few wineries in Priorat. The drive from the city is a relatively short, pleasant one, until you turn on the narrow, bumpy dirt road that is. Then, it becomes the treacherous ride that almost repositions one’s internal organs. Merely two hours away from Barcelona’s bustling urban sprawl, yet Priorat offers an expansive vista of serenity; it is an all-enveloping tranquility where one gets the feeling time has stood still here. It is not just its appearance according to my tour guide, Jordi, at the Devinssi winery. “Clamor of modern living has not quite encroached on the equanimity of Priorat; only a few basic modern amenities have made it into the local life,” Jordi told me. Perhaps it is the unforgiving heat that lulls one to slow motion. Nevertheless, Barbier and Palacios must have been quick to recognize the unique nature of the landscape. Protection offered by the Serra de Montsant mountains in the northwest, with altitudes reaching one thousand meters, endowed with the flow of rivers Siurana, Montsant and Cortiella and the unique llicorella soil that is wretchedly poor and unable to retain water must have been well appreciated by these two to set up shop and plant their vines. To paraphrase the political slogan of the early 1990s, it is the soil, stupid! Llicorella, which means slate in Catalan, is nutrient poor and free draining. The struggle of the vines to reach the depths of the soil for water is almost audible in the stillness of the burnished land. It is this tussle for survival that helps keep yields low and concentrate the minerals in the soil into the grapes, hence the rich, high-quality wines.

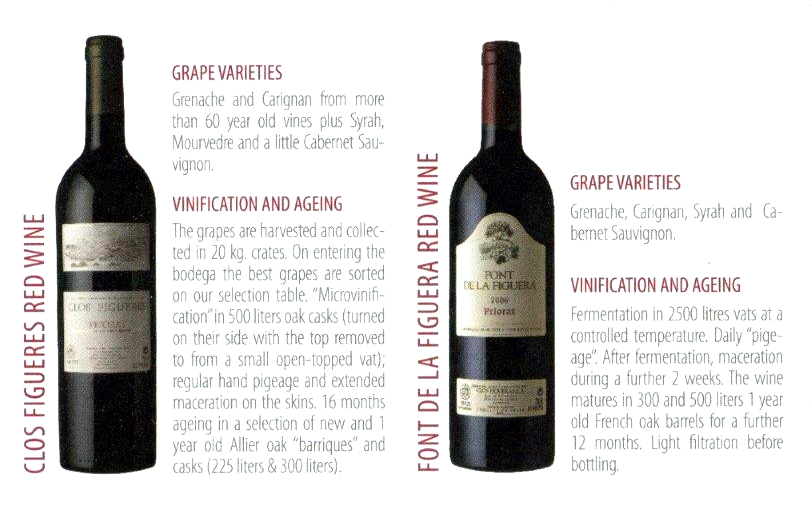

Today, Priorat is one of the two DOCa’s (Denominacion de Origen Calificada), the highest designation for a wine region by Spanish wine laws – the other contender for the prestigious title being none other than Rioja. The ethos of “quality over quantity” set in motion by the early gurus in the 1980s is still observed with as much vigor, producing some of the most acclaimed wines in Spain. Grenache, Carignan, Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon and Tempranillo are skillfully blended to produce wines with exalted quality to commend high prices in the international markets. Clos Figueras, one of the wineries I toured and had lunch, is one example. They had an exquisite selection of wines to taste. For my lunch I ordered Clos Figueras red wine, a blend of the usual suspects – Grenache, Carignan, Syrah, Mourvèdre and Cabernet Sauvignon – was an excellent accompaniment to the lamb dish (Cordero al horno) and the traditional sausage (butifarra parraillada).

As the region has gained popularity, the acreage of vineyards in Priorat has also increased over the last few decades, as well the number of wineries – pushing one hundred, if not more (I have been given different numbers). New winemakers, offspring of the original leaders included, are set to carry the torch for Priorat, in the footsteps of their elders. As high a quality of Priorat wines as still is, there is a distinct swing in style from those earlier days, however. As wine palates worldwide are turning to lighter, more fruit driven and less oaky styles, Priorat winemakers are taking note of the changing consumer preferences. Wines now express more fruitiness, have less oak and less alcohol to the extent hot climate permits. Clos Martinet is an example of this new trend. The winery was established by one of the original pioneers and is now operated by the daughter, Sara, who is clearly defining her own style by reducing reliance on oak and incorporating inert fermentation vessels into her winemaking. This new trend is not specific to Priorat, as it turns out. Other wine regions are also very conscious of the market demands, and are aiming for lighter, more fruit forward styles. Emporda wine region by the French border is an example. I had the opportunity to visit Mas Llunes winery in Emporda on this trip as well. The hostess, Miriam, was quick to mention with a proud wink that their wines are lighter, fresher, and fruitier than Priorat’s, as she was giving a tour of their scenic vineyards.

All told, Priorat is an inspiring success story… a tiny piece of land tucked away in the shadow of the prominent Serra Montsant mountains rising from obscurity to international recognition in just a few decades…salut to the trailblazers for appreciating the promise of this unique land and harnessing its potential.