Chips and grapes: the eclectic heritage of the Santa Clara Valley

Silicon Valley is arguably one of the most renowned places in the world. It owes its claim to fame as the birthplace of revolutionary ideas and groundbreaking innovations developed by technical visionaries dreaming of an improved future. However, prior to the “argonauts of technology” appearing on the scene merely a few decades ago, the valley offered a long, rich, culturally, and ethnically diverse history, including pioneers of some excellent wine making.

The area known today as Silicon Valley extends from the southern part of the San Francisco Bay to the city of San Jose – third largest city of the State, the tenth in the country and the State’s first capital. Much of it lies in the Santa Clara Valley. The valley was once a major fruit growing area, covered with vineyards and orchards, so much so that the British field marshal Lord Kitchener dubbed it as “The Valley of Heart’s Delight” during a visit to the area in the 1890s. The name stuck.

The area known today as Silicon Valley extends from the southern part of the San Francisco Bay to the city of San Jose – third largest city of the State, the tenth in the country and the State’s first capital. Much of it lies in the Santa Clara Valley. The valley was once a major fruit growing area, covered with vineyards and orchards, so much so that the British field marshal Lord Kitchener dubbed it as “The Valley of Heart’s Delight” during a visit to the area in the 1890s. The name stuck.

The prime “fruit basket” of a bygone era is now the global hub for high technology, invention, venture capital and, of course, the latest developments in social media. The region, given the moniker “Silicon Valley” by the electronic news journalist Don Hoefler in 1971, largely owes its existence to Stanford University’s engineering school. During the 1940s and 1950s, the legendary Dean of Engineering, Frederick Terman, encouraged graduates of the program to start their own companies paving the way for the transformation of the Valley from orchards into today’s entrepreneurial Mecca. The early pioneers of the “silicon” revolution that turned the Valley into a hotbed of cutting-edge technology were followed by countless others in the following decades, and the high paced, competitive evolution continues unabated today with familiar global giants like Facebook, Amazon, Google, Uber and many others. These high-tech companies have transformed our daily lives in unimaginable ways; for better or worse, we rely on the technology they have created for just about every aspect of our lives – from entertainment to transportation, to planning our next vacation. The Silicon Valley ethos of “thinking outside of the box” has attracted the world’s foremost creative minds throughout the last several decades. But even before the technology explosion, its mild climate has drawn people to this stretch of fertile land through the prior centuries.

The indigenous Ohlone Native American tribes were the first inhabitants of the area over four thousand years ago. They made a comfortable home for themselves, living off the bounties of the rich land. They were the first ones to exploit the mineral deposits of cinnabar found in what is now the Almaden valley, long before the arrival of Spanish explorers and the onslaught of the gold rush.

The Spanish explorers were equally struck by the mild climate of the region. Upon arrival, they quickly observed the similarities with their home on the Iberian Peninsula – the temperate Mediterranean climate moderated by coastal fogs, especially during the crop-growing season. This had to be the place for their twenty-one Missions, stretching from San Diego in the south to Sonoma in the north. The eighth which was built in the heart of the Santa Clara Valley in 1777 marked the beginning of wine making in the area, even though this was not the Missionaries’ prime occupation; their immediate interest was to create self-sustaining pueblos. The Spanish missionaries could not have failed to be impressed by the abundance of the wild grapes, “Vitis Californica”, especially along the area’s main watercourses. Their widespread usage of the Spanish word “uvas”, which means grapes, to name creeks, places, and canyons, is a clear testament to the prevalence of the fruit in the Valley. The wine produced from local grapes, which was called “Mission grape”, was mainly used for religious purposes and was not of particularly good quality, but it met the current need.

As the new century rolled on, it brought with it remarkable changes to the ethnic makeup of the Valley – diversification of the population, which had already been triggered by the “Gold Rush” in mid-century, was to include a different wave of newcomers. The political winds sweeping through France, combined with the news of gold in San Francisco, attracted many a Frenchman to purchase a one-way ticket to San Francisco; their original intent for the cross Atlantic journey being to find instant wealth. However, just like the Spanish explorers before them, they soon realized upon arrival that the valley, with its mild climate and propitious soil composition, offered an alternative living – one more predictable than the mining of gold. Grapes could be cultivated, and wine could be made following the tried and tested methods learned in the old country. It did not take the French immigrants long to recognize the inferiority of the local Mission grape and the need for importing improved European varieties. The contributions of the French to the valley’s viticulture were not limited to the introduction of new European cultivars, but they also introduced more sophisticated cellar techniques. It is fair to claim the arrival of the French marked the beginning of a serious viticulture revolution and laid the foundations of the wine industry in the area. The fortunes of the Valley’s nascent wine industry were concurrently impacted by two other factors – the completion of the South Pacific Railroad and even more consequentially the destruction of European vineyards, mostly French, by the phylloxera root louse across the ocean. It was catastrophic; almost sixty percent of the vineyards in France were decimated by the epidemic in the latter half of the 1800s. Lower quality wine in France as a result of the decimation of vineyards, buttressed the demand for the local California product. The combination of these factors meant the stars were aligned for the wine industry’s boom in the Santa Clara Valley.

Frenchmen put their indelible imprint on the Valley’s “wine revolution”, many of whom and their individual contributions are recognized and chronicled in detail by eminent wine historians such as Charles Sullivan and Thomas Pinney. The attraction of the land and climate was certainly the common denominator for the fortuitous assembly of these Frenchmen in Santa Clara valley, as much as the good “old boys’ network” and family alliances through marriage. The serendipitous debut of Charles Le Franc to the Valleys’ wine scene, whom Charles Sullivan rightfully calls the “father of the commercial wine industry in the Santa Clara Valley” is a case in point. Charles Le Franc arrived in San Francisco in 1850. It was through his ties with brethren from the old country, he ended up marrying the daughter of a French winemaker, Etienne Bernard Edmond Thee. This was his introduction to viticulture in the Valley. With a half share interest in his father-in-law’s property in San Jose, he built up and improved on what was already in place by planting European varieties and introducing sophisticated vineyard management techniques. His legacy can be found today in what remains of the “New Almaden Vineyard”. The original main winery building is protected as an historical heritage site in the midst of sprawling suburbia. Currently, there is some effort to turn the old building into a wine museum. The Friends of the Winemaker, a Los Gatos based organization, founded in 1976, with the purpose of preserving the history of wine making in the Valley, is working on refurbishing the building for this purpose.

Paul Masson, who eventually became to be celebrated as the “Champagne King of California” is another pioneering icon. Masson, with his famous slogan “we will serve no wine before its time”, often featuring Orson Welles in his advertisements, is a French immigrant from Burgundy, born and raised in a winemaking family. He arrived in the Valley with the dream of producing his California Champagne one day. His dream was to be facilitated through a meeting with Charles Le Franc – partnering with him first and later marrying his daughter, Louise.

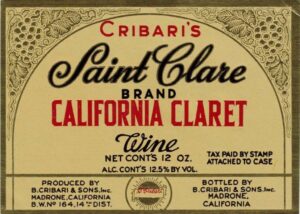

The early 1900s ushered in another torrent of immigrants from Europe. Italians, from all parts of Italy, including Sicily, Tuscany, Calabria and Piedmont, looking for refuge from the political turmoil in their motherland, poured into the United States in ever increasing numbers. Many Italians chose the Valley in California because of its mild climate and abundance of fertile land, mimicking the French half of a century earlier. Their arrival coincided with a need to expand vineyard acreage. Phylloxera’s decimation of the vineyards in and around San Jose, coupled with an increased demand for wine at sensible prices, promoted an increase of new land, free of this deadly louse, dedicated to the growth of healthy vines. In the South Valley, the area around today’s Morgan Hill and neighboring San Martin were an obvious choice; land was readily available at economic cost. The confluence of these factors created a vibrant Italian community of winemakers, stretching from Morgan Hill all the way south through the Hecker Pass. Many family-owned wineries, large and small, sprung up in the area. Most did not survive, struggling to stay alive through the twists and turns of the market, and severely impacted by the years of Prohibition. One, founded by Emilio Guglielmo from the Piedmont region of Italy, is today the oldest of the Valley’s wineries owned and operated continuously by the same family. Emilio Guglielmo not only survived the trials of Prohibition but became a major voice in the industry to find innovative ways of weathering the difficult years. The story is often told of how a hidden trapdoor connected his bedroom to a secret wine cellar! A few other wineries survived the Prohibition years, such as Morgan Hill Cellars established in 1913 by the Colombanos and the Kirigin Cellars founded just three years later by the Bonesios. These wineries are still in operation today. However, unlike the Guglielmo Winery, they have changed ownership over the years and are no longer operated by the founding families – some have not even retained their original names. One of these – the Malaguerra Winery – one of some twenty-six in existence in the region at the turn of the century, survives in name only as Morgan Hill’s Malaguerra Avenue.

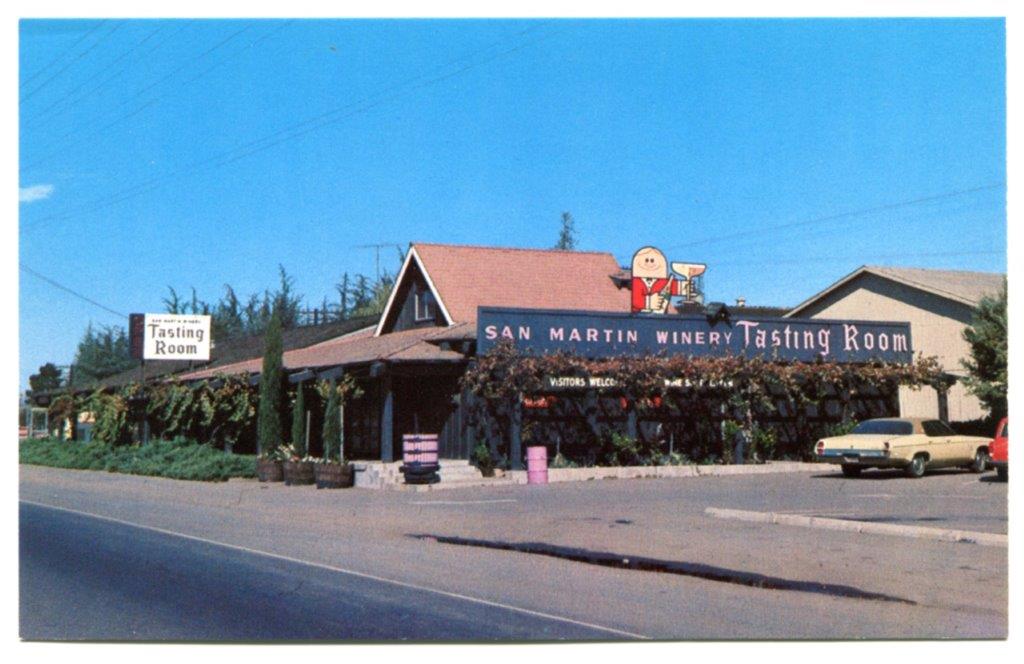

It is interesting to compare the respective contributions of the French and the Italian immigrant communities to the Valley’s wine industry. The French were indisputably the force behind the industry’s origins, making the leap from the Mission to European grapes. Despite their later appearance on the scene, however, the Italian winemakers would become a more powerful force, in part perhaps because of the sheer size of the Italian community. There is, as the saying goes, strength in numbers! The inherent Italian sense of a tight-knit community allowed them to organize and fund newly emigrated families in their endeavor to achieve a foothold in the Valley. After all, the banking industry giant Bank of America was founded by an Italian American, Amadeo Giannini, with the express purpose of providing loans to Italian immigrants who could not obtain funding from other financial institutions. Andrea Sbarboro was another dominant figure of the times who focused on promoting the new emigres’ success in the wine industry. His efforts in providing wine workers with ownership through his San Martin Winery, founded as a cooperative for grape growers in 1892, ultimately failed, but he was nevertheless a unifying voice for the Italian community and became a leading spokesman for wine and temperance during Prohibition.

All said, Silicon Valley presents a colorful historical panorama, spanning the Ohlones to the Spaniards to the high-tech revolutionaries and the region’s rich wine history, which is more vibrant than ever today. Even though for many people the phrase “California wine” evokes the image of rolling Napa vineyards, the Santa Clara Valley offers a wide selection of exquisite wines from winemakers dedicated to their art. History has a habit of repeating itself. Despite the demise of most of the Valley’s pioneering wineries of the late 1800s and early 1900s, it is gratifying to observe the current renaissance now playing itself out. The Valley is currently experiencing an exciting boom with a host of new winemakers from a wide variety of backgrounds all converging in the valley. Just as in the boom years at the turn of the twentieth century, today’s “pioneers” are trying their chances at wine making – some high-tech professionals in their previous lives, like the owners of the Aver Family Winery, Clos Le Chance and Satori, to name a few, or medical doctors, such as the owners of the Verde Winery. It is especially exhilarating to see female vintners joining what has historically been a predominantly male field. Ex-Weather Anchorwoman from a local TV station, Janu Goelz, has built up a quick reputation for her wines as the proprietor of the Alara Cellars, just as the winemaker of Lion Ranch Vineyards, Kim Engelhardt, contributes to the Valley’s success with her Rhone varietal wines.

Life is wonderful when ardent winemakers make great wines for us to enjoy…cheers!